The (Almost) Perfect Level Design of Thief II: The Metal Age

Despite one almost fatal flaw in its final mission, Thief II: The Metal Age contains some of the most purposefully crafted and well-designed levels of any game you could hope to play.

This is the 2000 sequel to 1998's

Thief: The Dark Project, which was a stealth-based immersive sim from

Ultima Underworld and System Shock creators Looking Glass Studios.

These are first person games where the objective verb is to

infiltrate, and the best approach is usually to avoid combat while

focusing on lockpicking and looting.

The second game features almost exactly

the same gameplay and player abilities, but sees the lead character

Garrett more focused on breaking into mansions, banks and other

well-guarded locations around the series' steampunk The City, as

opposed to delving into tombs and fighting off monsters. The horror

atmosphere of the original is largely absent though not entirely, but

as far as creating a simulation of being a thief with the tools to

rob from the rich and pay the rent, the design of the environments

and objectives is nearly spotless.

In contrast to the first game, where

the story came first and levels were created to support it, for Thief

II the team designed a series of levels and wrote the story around

them. This is a design-first game, which likely contributes to its

stately pacing and structure.

Unlike some other immersive sims where

players can generally eschew stealth in favour of a violent approach,

direct confrontation and combat is very challenging. Garrett is

pretty fragile, and sword blows from the startled guards will knock

his health down at an alarming rate. As far as being an immersive sim

goes, this is more about different approaches you can take with the

qualifier they have to be stealthy, and about a simulation and

engaging realisation of the game world you inhabit. The levels are

built in such a way as to encourage expression via different routes

and optional areas and objectives, so that players can still find

their own “path of least resistance” within the more prescriptive

abilities open to Garrett.

The key mechanic of these games is the

light gem at the bottom of the screen that dims or brightens

depending how much light you are stood in and how fast you are moving

– as you play you become accustomed to paying attention to this

constantly as it will inform how well guards can see you. Combined

with this is an NPC scheduling system that, well before The Elder

Scrolls IV: Oblivion, would have guards and other characters moving

around levels of their own accord on patrols of varying routes and

complexity. Being aware of where you are, where NPCs are, and where

you have observed they are likely to be, is key to playing the game.

You also make different levels of noise

depending on what you are walking across. The game employs genuine 3D

sound, simulating the way real noises bounce off surfaces in its game

world. Eric Brosius and the sound team worked with the Dark Engine to

give different areas or “room brushes”, different acoustic

properties. My source for this is the fandom

wiki, where you can also look at some of the various audio

environments. The result is that when playing the game, you could

close your eyes and know what surface you are walking on.

Do note that although I am mostly not

discussing the story, there will be complete spoilers for how the

missions themselves play out – and those levels are arguably the

most joyful discoveries you will have playing this game, so fair

warning if you haven't tried this 20-year old classic yet.

Abilities that change how you move

through levels

Garrett does have access to a range of

tools and equipment. This includes mines to use as traps, either

lethally or not, flares to light up darker areas (this is an

extremely gloomy game at times), and most significantly arrows with

elemental properties. These can be used to create new paths – there

is a water arrow that can be used to douse torches, creating new

patches of shadow for Garrett to skulk through, and rope and vine

arrows that, once embedded in a surface, will unspool a length of

rope or vine to climb up and gain higher ground. This is provided at

the beginning of each mission, and you can add to it with the loot

you picked up in the last level.

The kicker is, you only have one chance

to use your gear – encouraging the player to experiment and try

different ways of overcoming or circumventing the guard arrangements

and security systems.

The levels, which are designed in such

a way as to allow replays to have an altered journey through them,

may encourage a player to prioritise a certain gear purchase when

they play again, or if they save themselves into an impossible

situation and have to restart anyway. Some might have a lot of loud

floors so you would want to take more moss arrows to soften your

footsteps on those surfaces, others are particularly well lit so you

need more water arrows to extinguish the torches, and so on. Perhaps

a well-placed rope arrow would create a path that circumvents an

encounter you had trouble with.

What this means is that you are getting

more out of the game if you do play again, having a different

experience, and knowledge of the layouts is meaningful and rewarded.

Also, if you do find a level too hard restarting might allow you to

swing the odds in your favour with your gear choices.

Thief II's levels – spaces that

feel real

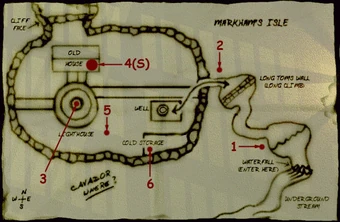

The levels in Thief 2 resemble real

places rather than corridors or video game environments. Viewed from

above, these resemble the charming little maps Garrett often takes

with him, which in the fiction he has either purloined from an

insider or sketched based on what he knows of the place he's about to

hit. The map is a very clever inclusion especially when combined with

the compass you have, which is an item on your hotbar that swings as

you turn. So the levels are built to support true-to-life compass

navigation via a drawn map you can pull up. Not to mention - and why don't games do this more often - you can annotate your map! Being able to personalise this resource can be huge, particularly in later levels which can be both enormous and labyrinthine.

There is a lot of environmental

storytelling on offer with readables, signs, notes, books and more

that provide narrative and detail on the people who live and work in

these spaces – thorough players can begin finding out about key

characters and factions almost before they are properly introduced. A

perfect example is the early “Shipping... and Receiving”, where

each warehouse you open doesn't just reward you with the loot the

person had stored there, but information about who they are and what

they're up to.

You'll have a variety of methods of

ingress, including crawlspaces, rooftops, back doors and more. Some

areas have very open spaces while others are enclosed, making it more

difficult to avoid notice and reducing the visibility advantages you

often have over the guards. The guards themselves – and the robots

and monsters that are introduced with surprising narrative deftness –

may be stationary or patrolling. The levels are also designed to

enable you to ghost them if you want to, with each guard patrol or

security system offering at least one exploit for the player. On

harder difficulties you will often be failed for knocking out guards

even non-lethally. Streets, corridors and rooms are designed to

enable guards a pretty good view of most of it, most of the time, so

that with timing and by taking advantage of patches of shadow Garrett

can effectively sneak past.

All of these elements of design and

gameplay are brought to bear in a series of 15 missions that, for the

most part, make exceptionally good use of each to guide the player

through an escalating series of challenges and rewarding experiences.

One of the best first-fifths in

gaming

The opening three

levels ingeniously introduce gameplay and up the challenge in stages.

Unlike the first game Thief II doesn't feature a training level, but

the opening mission does an excellent job of tutorialising the

gameplay. While still shaped like a real place, 'Running

Interference' gently pushes players through the Rumsford Manor in

almost a straight line. Unusually, Garrett starts off with a key –

which opens one door on the other side of the manor from his target,

his friend's captured fiance who he must rescue. This linear

infiltration introduces each mechanic in turn, with a few different

arrangements of guards near generous pools of shadow so the player

can get accustomed to alertness levels and taking advantage of hiding

places in a low risk way. On normal difficulty, exploration of the

second floor of the mansion is completely optional – deftly

introducing the idea that pushing around the edges of levels will be

greatly rewarded.

'Shipping... and

Receiving' opens up, giving you a large open area to explore. With a

cleverly simple hook – Garrett needs to steal enough money to be

able to pay the rent – you are dropped into a warehouse district

and can make your own path around the area to complete this

objective. You can explore however you want, with a number of points

of ingress to the warehouses that will eventually bring you to a

central control room from which to open the lockboxes. Readables

found throughout the level and a hint you can buy beforehand will

clue you in to where the best loot is found, and you basically choose

who you want to rob and then go. Or, rob everyone and have more money

for gear in the next level.

'Shipping... and

Receiving' opens up, giving you a large open area to explore. With a

cleverly simple hook – Garrett needs to steal enough money to be

able to pay the rent – you are dropped into a warehouse district

and can make your own path around the area to complete this

objective. You can explore however you want, with a number of points

of ingress to the warehouses that will eventually bring you to a

central control room from which to open the lockboxes. Readables

found throughout the level and a hint you can buy beforehand will

clue you in to where the best loot is found, and you basically choose

who you want to rob and then go. Or, rob everyone and have more money

for gear in the next level.

It provides a

feeling of freedom and possibility that, this early in the game, is

formative. The level is well placed (in contrast to the first game's

second mission 'Break from Cragscleft Prison' which is quite linear

and hostile). It showed me that I could expect locations to offer a

number of ways for me to get into them and back out again, and that

beyond the completion of my objectives, how much longer I spent in a

level would be largely up to me.

The third level,

'Framed' (full writeup here), is where Thief II begins to play some of its best cards.

You are infiltrating a police station, and compared to the warehouse

district the player is now closed in by a tighter and more

restrictive environment which necessitates a hall-by-hall and

room-by-room puzzle solving approach. Robotic security systems are

introduced as well.

However the ace up

the sleeves of the designers for this level, Rich Carlson and Rob

Caminos, is that even on the Normal difficulty, you'll fail the

mission if you knock out more than five guards. This partially

enforces a “ghosting” style of play. Part of the thrill of these

games is getting past guards without them ever knowing anything was

wrong, but some players (myself included) might initially be too

nervous to leave the guard wandering around and so knock them out and

hide them in a corner. Having a restriction like this placed on me

not only encouraged me to shake up my playstyle, but felt like the

game was saying to me that I could do this, if I just gave it a try.

As a result I

began moving more quickly and confidently around the level, taking

care to memorise where guards were and prioritising those that were

likely to cause the most trouble if left to wander about. This had a

permanent effect on the way I played the game, and for the remainder

of the 20hr campaign I was much more comfortable efficiently moving

around guards and staying out of their sight rather than feeling the

need to knock them out. The level's objectives had made me develop

the approach I needed to get through the game.

This opening fifth

of the game makes the player feel like a thief by showing them how to

overcome or work around each obstacle with the right plan of action,

and guide the person playing towards a style of play that best fits

the power fantasy of moving through a space completing a task while

hostile forces are completely unaware.

A campaign packed with standout

missions

The game's middle sections feature

several banner examples of Thief II levels that put these abilities

to the test, such as First City Bank and Trust, a large but enclosed

stealth playground with dense options for routes and solutions.

There's Blackmail, which brilliantly changes the objective partway

through with an unexpected twist. 'Ambush' is a large area of The

City, and along with the rooftop-scouring Life of the Party is an

antecedent to the level design of Arkane Studios' excellent

Dishonored games. The latter is particularly notable for how it

constantly makes the player feel like they are taking an unusual

route or sequence-breaking even if they are largely tracing the route

the designers had in mind – the journey feels organic. This is an

example of where environments being designed to resemble places

rather than video game levels contributes to the suspension of

disbelief. This also provides an empowering feeling of navigating

with real-world logic across a topography that isn't built to be

crossed – and that the enemies and other NPCs in the level would be

unable to traverse.

A highlight is Precious Cargo, which is

a mix of haunted house, submarine and secret base, with the ghost of

a long-dead pirate lurking hidden somewhere in the level, tragic

fates to discover in the environment's readables, and a suitably

creepy lighthouse to ascend. There are many different surfaces, from

soft mulch to the metal of the submarine, requiring the player to

constantly assess their surroundings and consider their path, and the

diverse environment offers interiors, wide open spaces, verticality

and even subaquatic exploration of the gigantic wireframe with an ebb

and flow of tension. Fittingly, this is one of the levels in which

Garrett must fill out his map as he goes, adding to the sense of

learning about the area and gradually having the knowledge to quickly

move about and get things done. Murky waters and atmospherically

limited draw distances plus the soupy overcast colour palette add to

the creepy vibe and the sense that Garrett and the player are far

from their established environment of mansions and back alleys.

Everyone talks about Life of the Party, but this was my favourite

mission.

Educating the player with levels

that have a lesson to impart

The game seems invested in teaching the

player. Even past the opening three missions and their immaculate

tutorialisation of the gameplay, Thief II has a smattering of

missions that demonstrate specific ways to playing that will later

pay off in high-stakes situations and enemy-dense areas. Trace the

Courier has you re-traverse exactly the same environment as in

Ambush!, but you are shadowing a courier and so have to get through

the area very quickly and without getting into fights or slowing down

too much. You have to learn how to quickly and stealthily navigate

areas you might otherwise have taken your sweet time in. Trail of

Blood has you follow yes, a trail of blood, so that you always have

to be taking notice of the environment while quickly moving through

it – I got turned around at least once trying to be clever and

sequence-break.

Eavesdropping and Kidnap have randomly

generated elements in them, which apart from adding replay value seem

to be about goading the player to be reactive and formulate plans

based on what is in front of them. In the former you have to creep up

to the right door and listen in for the location of a key – which

could be in any of 14 locations and is randomised each time you play.

In the latter, your target could be in a number of places, and the

player has to use information they find along the way to deduce where

they are and what signs to look out for. These dynamic designs keep

the player on their toes and encourage a responsive approach.

Eavesdropping and Kidnap have randomly

generated elements in them, which apart from adding replay value seem

to be about goading the player to be reactive and formulate plans

based on what is in front of them. In the former you have to creep up

to the right door and listen in for the location of a key – which

could be in any of 14 locations and is randomised each time you play.

In the latter, your target could be in a number of places, and the

player has to use information they find along the way to deduce where

they are and what signs to look out for. These dynamic designs keep

the player on their toes and encourage a responsive approach.

The penultimate levels have elicited

mixed reactions based on what I've read online on forums and comment

sections, and from comments on the Inside at Last podcast about the

first two Thief games.

'Casing the Joint' and 'Masks' take

place in the same sprawling mansion, which Garrett must enter firstly

to fill out his map and examine the security systems, then return to

on the night of an exhibition of priceless masks to steal at least

one of them. The criticism is that this is the same environment

twice. 'Casing the Joint' enforces ghosting – you now can't knock

anyone out, and must move through a large indoors space without

aggroing anyone. The idea of memorising an area so that you can get

back across it quickly and efficiently is accurate to what a thief

might do when casing a ritzy manor, and fits with what I like from

immersive sims which is the feeling of gaining mastery over a space.

For me, these levels deliver on the

promise of being a thief, with high levels of challenge and a dense

combination of everything the player has already done. It is all

leading into something that will notch the difficulty up for a new

challenge – for better and worse, but the significance of the

mission's placement is that it is honing abilities the player is

about to absolutely need in the final mission.

A difficult final mission

Sabotage at Soulforge is either pretty

high or pretty low on players' lists of their favourite missions in

this game, based on forum-diving, and I also found a lot of posts

purely expressing frustration with it. It is fair to say that it is a

divisive denouement to a brilliant game. I had been warned that it

was a significant hike in difficulty, but I still wasn't quite ready

for what I found.

The first half of the mission requires

you to gather materials and items to craft a beacon, which is

plot-necessary in order to thwart the primary antagonist's plans. To

understand where to get the components, how to combine them and

where, you need to pay close attention to a sort of manual Garrett

will find early on. Meanwhile, the areas you will be visiting are

patrolled by a denser than ever concentration of high level enemies

and security systems – no matter how much loot you scrounge up in

the mission prior, you simply won't be able to knock out every guard

and disable every robot.

The sticking point is that the main

concern requires you to keep track of materials, items and what are

basically crafting stations throughout a gigantic map, and it causes

so much inventory tax that for me it got past the point of working

with the map and compass – which is good and fun – and became

very fiddly.

However, the final section redeems the

mission – and the final taste that the game leaves you with. Once

Garrett has his beacon, he has to change the signal for a number of

broadcasting points. On the normal difficulty you have to hit five of

a possible eight. This is very successfully done, as each area has

its own self-contained stealth challenges that are all different and

all pretty tough. They use different mix-ups of enemies, set-ups and

geography that the player has dealt with before, but with everything

turned up a notch.

So the enforced ghosting, navigation of

tight spaces at speed and use of various tools throughout the levels

has all been leading to this, where every ability the player has

developed will be tested. Using your map and compass to get from one

place to another and find the beacon points is another essential

skill that you've been well prepared for at this point. While the

beginning of the mission is not really representative of what the

game has been asking you to do so far, the final section is a well

designed final exam – particularly as players on the normal

difficulty can choose another of the areas to deal with if one

doesn't suit the play style they have developed.

Conclusion

Overall I found

this game to be a 101 in using mechanics to teach a player to make

the most of their abilities to overcome greater and greater

challenges. It is nearly let down by a hurdle at the end, which I

initially didn't enjoy and which feedback online suggests has been

off-putting for others in the many years since the game came out.

Fortunately, the back half of the mission is so strong that –

personally – I remembered everything I loved about playing the game

and was able to use almost everything I had learned in getting to

that point.

While

the sound design, sensation of being in a real place due to the

amazing blueprinting of each level, the replay value due to the

porous environments and multiple paths, the way the narrative unlocks

through readables and environmental storytelling is all masterclass

level, the structure of the game and how it builds up the player's

relatonship with the mechanics is what stuck with me.

Comments

Post a Comment