Consistency is Key: Physics, Real-World Logic and Emergent Play in Immersive Sims

In games like Deus Ex, Dishonored, Thief, Prey and more, consistent physics and systems mean you can use real-world logic and engage in emergent, improvisational play

A sophisticated physics engine is one of the stalwarts of immersive sim game design. Crates and objects can be piled up, elements like fire and water can be interacted with realistically, and in general the physics of the world around the player are simulated in such a way as to be used in both exploration and combat.

This means that unlike an adventure game where for a particular puzzle you might get a button prompt to douse a torch, if you can use water to put out a torch in an immersive sim, you can do it for every torch in the game. The physics of the game should be consistent. A vine arrow in Thief doesn't just stick to a few predetermined surfaces chosen by the designers – it will stick to every surface in the game, dropping a rope of vine that the player can then climb up. (This is one reason why Thief 2014, which had only a few highlighted points the player could attach their rope arrows to, was considered by the hosts of the Inside at Last podcast to have lost some of the immersive sim qualities that made the originals so special.)

One of the things you can easily forget is that you can use real-world logic, instead of video game logic. We're so trained by years of playing games to expect low levels of interactivity and response in the environment.

However, as early as Ultima Underworld you could use a broom through the bars to get out of your cell. Use arrows to press buttons in Thief, or the foam bullet to do the same in Prey. This contributes to the feeling of breaking the game or taking the path of least resistance, or even “cheating” the game – even though it is intentional. And significantly, you do not break immersion by doing something unexpected. It is a fine balance of “the designer thought of everything” and “I'm going to do something they never even expected.” There is a lot of Dishonored content on YouTube that is emergent play, literally stuff the designers didn't think of doing. The two-way relationship players can have with designers via these games is something really integral to immersive sims.

This means you are encouraged to improvise. These games often want to show players that they can experiment, and that it is encouraged and rewarded. This means that by the time they are a few levels into the game, players are more likely to be examining the environment with a critical eye. Is there a way round this? What tools do I have that can obviate the obstacles in front of me? What if I just piled up objects to create my own path? Good immersive sim level design avoid prescriptive right or wrong answers and is instead reactive, based on consistent rules.

Ricardo Bare told Game Informer that if a player in Prey comes up with a plan to hack turrets, then use the Lift power to launch them up into the air in range of some patrolling Typhon, and the turrets begin to unload on the aliens – and the plan actually works, people feel like “I can do anything in this game.” The dev team did the work of putting in systems that (by and large) would do what was expected of them no matter what the player could think of.

What this means is that screwing up is fun. Like how failing a die roll is more interesting in D&D, failing in an immersive sim usually doesn't mean game over – usually something else will happen. Generally there are no fail states, other than death. Fail to sneak by someone, and you don't get the instant desynchronisation of an Assassin's Creed game – now you have to either fight your way out, find a way to confuse or stun your enemies while you run away, or come up with another way to combine your abilities and knowledge of the level to your advantage. To steal a quotable from Duckfeed's Gary Butterfield, a stealth system is as much as it is fun to get caught – and immersive sims provide you with ways to keep playing a fun game even after Plan A goes out of the window. Forced loss conditions were in fact avoided as one of Looking Glass Studios' core design principles.

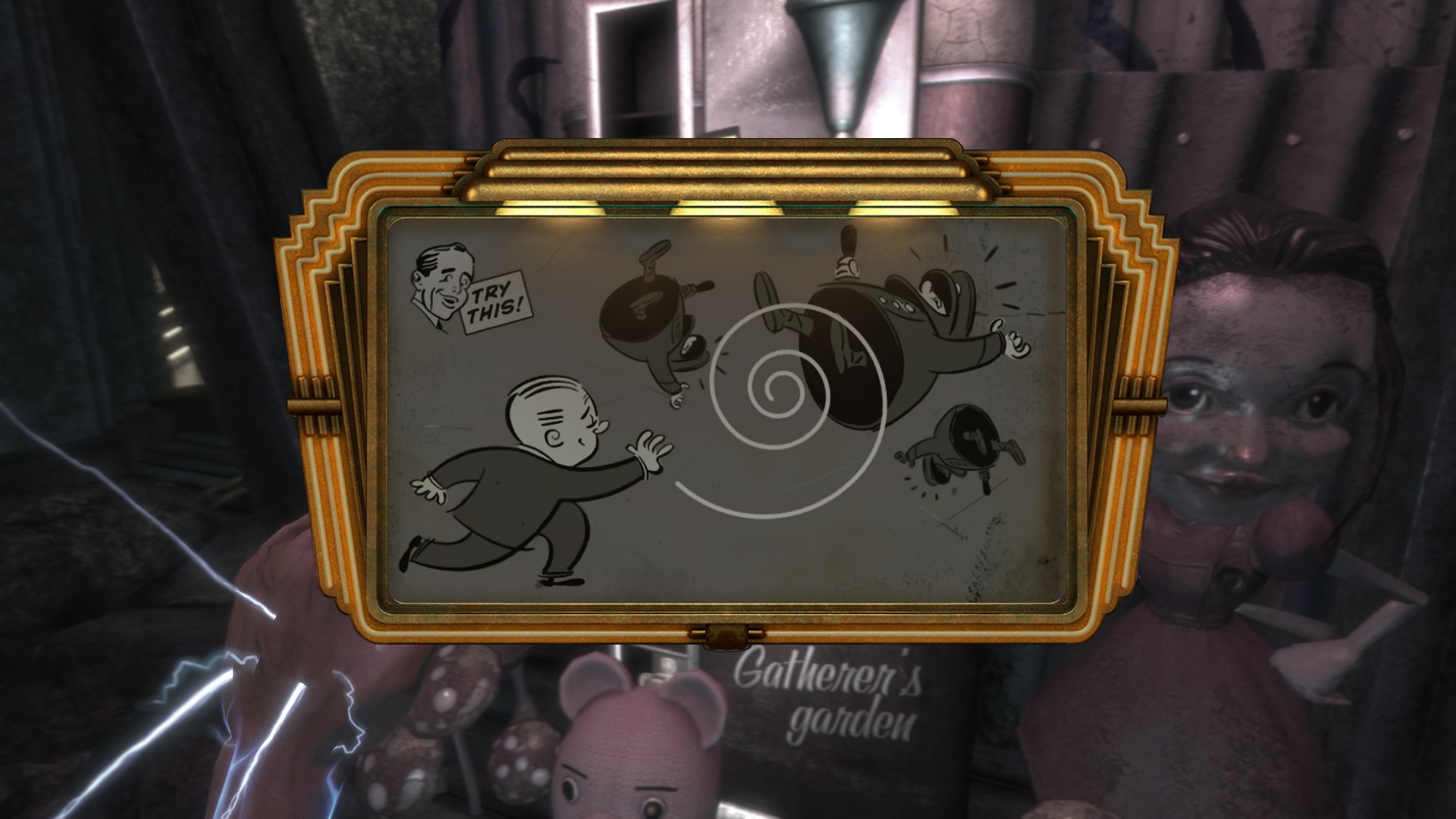

So play is not modal in these games – exploration, stealth, puzzle solutions and combat all bleed into each other because the world is a piece of clockwork that is happening around you, not a series of mode-based tracks with fail conditions if you don't abide by the rule-set they provide. Generally you don't get “gotcha” moments and are able to plan for things. For a pretty knotty encounter, 90% of your time “dealing with” something like the subway hostage situation in the early hours of Deus Ex could be planning what you are going to do. In a more fast-paced game like BioShock you might have to plan faster, but generally you'll develop a few plans of action to fall back on depending on the enemies you encounter.

"Time to crate" might represent a point at which designers ran out of ideas to some, but if they can be piled up and used to sequence break or generate a memorable and rewarding play experience, it might not be a bad thing. Which is lucky, because Deus Ex's time to crate is a few seconds.

Co-written - Jon and Dan

A sophisticated physics engine is one of the stalwarts of immersive sim game design. Crates and objects can be piled up, elements like fire and water can be interacted with realistically, and in general the physics of the world around the player are simulated in such a way as to be used in both exploration and combat.

This means that unlike an adventure game where for a particular puzzle you might get a button prompt to douse a torch, if you can use water to put out a torch in an immersive sim, you can do it for every torch in the game. The physics of the game should be consistent. A vine arrow in Thief doesn't just stick to a few predetermined surfaces chosen by the designers – it will stick to every surface in the game, dropping a rope of vine that the player can then climb up. (This is one reason why Thief 2014, which had only a few highlighted points the player could attach their rope arrows to, was considered by the hosts of the Inside at Last podcast to have lost some of the immersive sim qualities that made the originals so special.)

One of the things you can easily forget is that you can use real-world logic, instead of video game logic. We're so trained by years of playing games to expect low levels of interactivity and response in the environment.

However, as early as Ultima Underworld you could use a broom through the bars to get out of your cell. Use arrows to press buttons in Thief, or the foam bullet to do the same in Prey. This contributes to the feeling of breaking the game or taking the path of least resistance, or even “cheating” the game – even though it is intentional. And significantly, you do not break immersion by doing something unexpected. It is a fine balance of “the designer thought of everything” and “I'm going to do something they never even expected.” There is a lot of Dishonored content on YouTube that is emergent play, literally stuff the designers didn't think of doing. The two-way relationship players can have with designers via these games is something really integral to immersive sims.

This means you are encouraged to improvise. These games often want to show players that they can experiment, and that it is encouraged and rewarded. This means that by the time they are a few levels into the game, players are more likely to be examining the environment with a critical eye. Is there a way round this? What tools do I have that can obviate the obstacles in front of me? What if I just piled up objects to create my own path? Good immersive sim level design avoid prescriptive right or wrong answers and is instead reactive, based on consistent rules.

Ricardo Bare told Game Informer that if a player in Prey comes up with a plan to hack turrets, then use the Lift power to launch them up into the air in range of some patrolling Typhon, and the turrets begin to unload on the aliens – and the plan actually works, people feel like “I can do anything in this game.” The dev team did the work of putting in systems that (by and large) would do what was expected of them no matter what the player could think of.

What this means is that screwing up is fun. Like how failing a die roll is more interesting in D&D, failing in an immersive sim usually doesn't mean game over – usually something else will happen. Generally there are no fail states, other than death. Fail to sneak by someone, and you don't get the instant desynchronisation of an Assassin's Creed game – now you have to either fight your way out, find a way to confuse or stun your enemies while you run away, or come up with another way to combine your abilities and knowledge of the level to your advantage. To steal a quotable from Duckfeed's Gary Butterfield, a stealth system is as much as it is fun to get caught – and immersive sims provide you with ways to keep playing a fun game even after Plan A goes out of the window. Forced loss conditions were in fact avoided as one of Looking Glass Studios' core design principles.

So play is not modal in these games – exploration, stealth, puzzle solutions and combat all bleed into each other because the world is a piece of clockwork that is happening around you, not a series of mode-based tracks with fail conditions if you don't abide by the rule-set they provide. Generally you don't get “gotcha” moments and are able to plan for things. For a pretty knotty encounter, 90% of your time “dealing with” something like the subway hostage situation in the early hours of Deus Ex could be planning what you are going to do. In a more fast-paced game like BioShock you might have to plan faster, but generally you'll develop a few plans of action to fall back on depending on the enemies you encounter.

"Time to crate" might represent a point at which designers ran out of ideas to some, but if they can be piled up and used to sequence break or generate a memorable and rewarding play experience, it might not be a bad thing. Which is lucky, because Deus Ex's time to crate is a few seconds.

Co-written - Jon and Dan

Comments

Post a Comment